Article begins

The “social contract” seems to be returning as a popular concept in recent years, in academic, policy, and everyday contexts. For example, the Governmental Program of Gustavo Petro, newly elected leftist president of Colombia, has promised to build “a new social contract of buen vivir and well-being among all the nation’s diversity,” and the recent book What We Owe Each Other by Dame Minouche Shafik, director of the London School of Economics, calls for a “new social contract for the twenty-first century” to address the global issues of “polarized politics, culture wars, conflicts over inequality and race, and intergenerational tensions over climate change.” But what do people, those who are in positions of power, and those who are not, mean when they talk about social contracts?

An anthropological assessment of the social contract shows that state-society relations in different contexts are affected by the widespread idea that they are contractarian in nature, that states and people are bound by a deal they have made to each other. This “contractarian thinking,” as we call it, involves a set of implicit assumptions about how state-society relations should be, which becomes a yardstick against which people interpret their experiences as meeting or failing to meet those standards. Furthermore, actions of government actors are often shaped by normative ideas about social contracts. As such, we believe the social contract merits renewed attention, not to revive an outdated theory and begin new disputes over its precepts, but to recognize it as a sticky, alive concept, which travels and reappears in different guises, both hotly appropriated and enthusiastically refuted in different intellectual and lay contexts.

An anthropological approach to the social contract, as we argue in a recently published special issue in Critique of Anthropology, treats the social contract as an interpretative resource that impacts the lived experience of state-society relations, an idea that people around the world live with about how society functions, from village councils in India to state officials in Colombia, international digital nomads to Afghan refugees in Germany. The authors in the special issue explore ethnographic instances of both the explicit concept of the social contract and this implicit contractarian thinking on the ground.

Anthropology needs to explore the political power of the social contract as an idea.

Arguing that people’s ideas of states are shaped by contractarian expectations and assumptions, but their real-world experiences undermine these ideas, Sara Lenehan points out that Afghan asylum seekers fled Iran, coming to Germany after changes in Iranian law left them with fewer rights, because they heard Angela Merkel saying that refugees would be welcome. They were in search of a “more caring” social contract but were disappointed when the German state did not appear to be fulfilling their side and did not seem to treat “deserving” migrants fairly. Another article by Dave Cook depicts the “digital nomads”—middle class people from the global North seeking to live out a dream of freedom, doing remote work from exotic locations such as Thailand, untethered from any social contracts with states. Yet they find themselves mired in bureaucracy for visas, taxes, and online businesses, in relationships with many states at once, ultimately undermining the fantasy of being able to “opt out” of a social contract by leaving a country.

What about the people on the other side of the state-society relationship—the bureaucrats and officials who interact with society and create policies? In these cases, the social contract imaginings of those in power greatly inform the actions of the state, with inexorably political effects for their societies. Ben Bowles writes about how British civil servants promote the rhetoric of “resilience” in their policies about infrastructure, which shifts responsibility onto citizens and away from the state. Gwen Burnyeat details the way that Colombian government officials communicated the details of a complex peace accord to the public in a rational-technical manner, then analyzed the loss of a polarizing referendum, which rejected the accord, as due to their having not been “emotional” enough. This reveals a contractarian ideal of state-society relations as above politics.

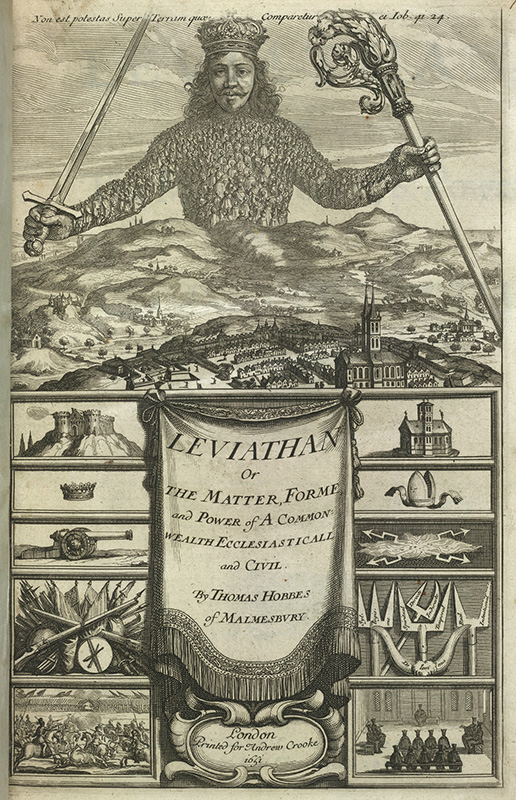

It is important to study contractarian ideas in the real world, but ethnographic analyses of the social contract must also reckon with its philosophical canon, because how and why ideas evolve and travel matters in understanding the political projects they engender. Though its roots go back to ancient Greece, social contract theory consolidated as a strand of European political philosophy in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Broadly speaking, it is the idea that organized society is formed by individuals who make a common agreement to regulate their coexistence. The most famous contractarians—Thomas Hobbes, John Locke, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Immanuel Kant, and later John Rawls—imagined varied versions of the social contract, all rooted in different assumptions about human nature, such as peoples’ propensity for violence or peacefulness, desire for freedom, and ability to reason, and they used their models to determine the political legitimacy of governments.

Social contract theory had many critics throughout its heyday. Some attacked the idea that people had at some mythical point in the past got together and founded society and the state (though most contractarians did not take this idea literally). Others thought that the contract as a logical explanation for political consent to authority in perpetuity was unsustainable. Hegel and Marx (for Marx’s critique see Lessnoff) both rejected contractarianism for its vision of a pre-social individual, with pre-cultural morals and concepts. Later, the communitarians, such as Michael Sandel and Alisdair MacIntyre, argued that neither the individual nor their conception of the good could exist outside society. But while the social contract as a basis for political legitimacy may be internally flawed, as an idea it continues to exercise considerable influence on political life around the world, as illustrated earlier by the quotes above from leading political figures and institutions.

The push for change in the political statements detailed above and the real-world impacts that understandings of the social contract have in everyday life are impacted by the continued use of a problematic model. As anthropologists, our interlocutors in our ethnographic fieldwork are also philosophers and thinkers, sharing the same world of ideas that we inhabit. While the social contract has infused much analysis in the social sciences and it is important to examine our own analytical tools, it is not a concept that stays within academia: contractarian logics permeate multiple spheres, shaping many of the political formations we have today. Organizations, politicians, policymakers, activists, and all kinds of communities invoke the idea, giving it different inflections and translating it into grounded common sense, with a variety of effects.

Anthropology needs to explore the political power of the social contract as an idea. But rather than asking, as so many politicians, academics, and lay people today seem to be, whether social contracts are broken or if we need new ones, we should instead ask how we socially construct the idea of there being a social contract there to break in the first place, and what the political effects of this idea are in different contexts.