Article begins

On the International Day for the Elimination of Violence Against Women (November 25, 2019), the Chilean feminist collective Las Tesis grabbed the world’s attention by performing “Un Violador en Tu Camino” (“A Rapist in Your Path”) outside Chile’s supreme court. Within months, it was reproduced hundreds of times in 52 countries. American women performed it outside Harvey Weinstein’s trial. Female Turkish lawmakers sang it in parliament.

“Patriarchy is our judge/That imprisons us at birth.” Chant the blindfolded women. “And our punishment/Is the violence you don’t see.”

Why did this song resonate across cultures? In an interview, Paula Cometa, a member of Las Tesis, points to an answer: Women’s experiences of violence are ignored by state actors—the police, courts, and lawmakers.

In researching and creating the song, Cometa said the group discovered that rape, other violence, and even killing of women just “fade away in the [criminal justice] system.” Impunity for femicides extends across Latin America, where misogyny translates to negligent investigations and weak punishment for perpetrators.

Globally, the phenomenon of missing data about femicides has been identified as a problem for at least a decade. In 2008, the nonprofit PATH, the World Health Organization, and other NGOs published a joint report which showed that official information on femicide is often incomplete, inconsistent, and “significantly underreported in every region.” Barriers to accurate reporting include incongruencies between the numbers reported by police, justice systems, hospitals, and mortuaries. Furthermore, the absence of a standardized definition for “femicide” makes global data comparisons difficult.

At RAND, we began looking for alternative ways to track femicides in January 2020. We first examined whether Latin Americans’ perceptions of violence could predict country-specific homicide rates. We found a statistically significant correlation between homicide rates and people’s perceptions of violence as a top issue in their country as measured by the Latin American Public Opinion Project (LAPOP) surveys. However, there were no significant patterns over time. This suggested the data patterns could be driven by country-specific variation in crime reporting rather than real differences.

Luke J Matthews

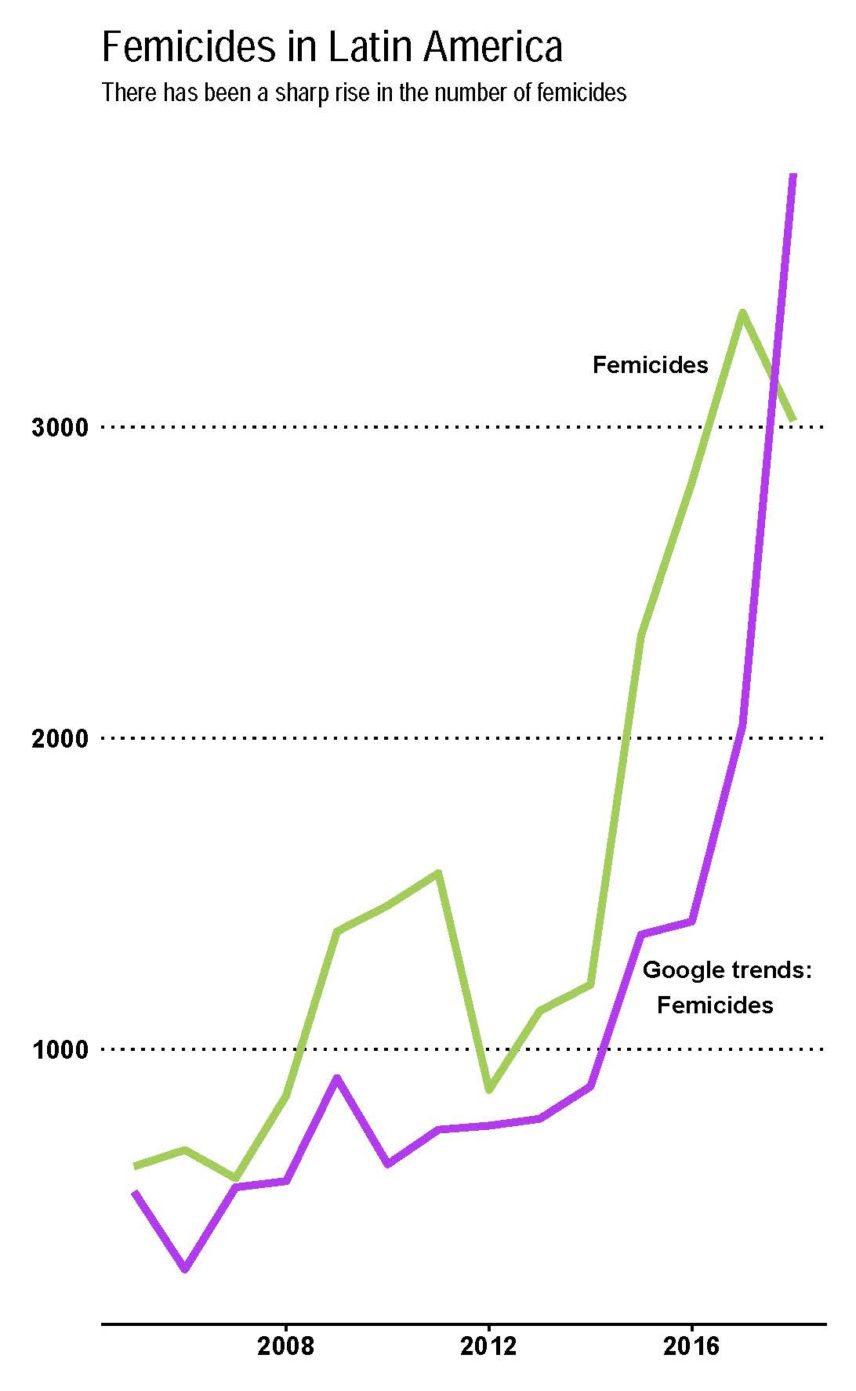

To see if we could try to fill in the missing data and discrepancies between governmental, NGOs’, and activists’ reports, we built statistical models from crowdsourced datasets like Google Trends, and GDELT. We found a strong correlation between femicide data from the United Nation’s Gender Equality Observatory for Latin America and the Caribbean and Google searches for the word femicidio. This suggests Google and other internet/social media search patterns and public opinion surveys can help us make inferences where data are missing.

Still, questions remain. In their book Data Feminism, authors Catherine D’Ignazio and Lauren F. Klein point out that crowdsourcing is a flawed way of gathering data because of noise in the sources and inherited biases in the data systems that collect them. While we see value in collecting (and sharing) such online femicide data because it provides a quick proxy for the scale of the problem, we also acknowledge that online data raise perennial anthropological questions about the objectivity of knowledge. Specifically, given the lack of precision in the data, we are unable to determine whether people’s perceptions are tracking real changes in femicide frequency, or whether the criminal justice system is responding to public pressure by accurately recognizing and recording crimes in official statistics. Relatedly, are perceptions of crime driving online discussions or are online discussions driving perceptions? With better data, anthropologists have been able to disentangle how cultural values and public perception predict the cultural evolution of governmental systems and to economic development. Improved data from diverse sources may enable improved understandings of femicide as well.

LasTesis were recognized by Time magazine as one of the 100 most influential people in 2020. They achieved what has taken years for other movements: a clear and resonant message about violence against women. We now also need new ways to generate and compile data to measure the scale of this ongoing crisis.