Article begins

What we talk about when we talk about Tinder.

Anne Chahine

I have never been good at dating. I simply refused to acknowledge the subtleties and rituals of courtship, to dance the dance that potential lovers perform when declaring their affection for each other. Luckily, I found a partner who announced his interest with clear and unequivocal signals.

Anne Chahine

When online dating first became popular, I was startled at how easy it seemed, a stream of men and women one after the other across the screen. Suddenly, love seemed to be at everyone’s fingertips. For most of us, digital forms of communication have become an essential part of everyday life. But how does dating technology affect the way we search for a partner? What happens once you step out of the online realm and into the world of face-to-face relationships? And how might it affect people’s perception of the dating process and even the very concept of love?

Anne Chahine

In 2015, I made a short documentary about the dating app Tinder, Looking for Mr. Right Now. I contacted people who might be interested in sharing their experiences and also searched for potential informants through the platform, creating a user profile complete with photograph and a short description of the project. I wanted to get at why people use Tinder and understand their sensory and embodied experience of engaging with the app beyond the tactility of mobile media (see Pink et al. 2016 for more on this).

Anne Chahine

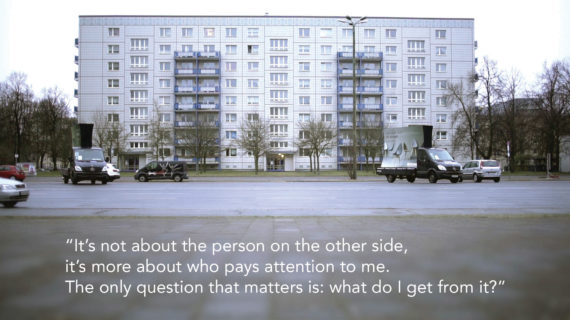

At first, the act of swiping a person’s face to the left (not interested) or right (interested) felt almost violent in nature and I took a long time to reach a decision. My right thumb had the power to influence the future of the project and I was reminded of Tim Ingold’s (2013) idea of the hand being the direct extension of the brain. But all these hesitations soon gave way to split-second decision making about who to choose and how to initiate a successful conversation. One of my interviewees coined the term “keep the love machine running,” when describing this almost routine process. The “machine” would then steadily work away in the background and hopefully produce a connection by the end of the day.

Anne Chahine

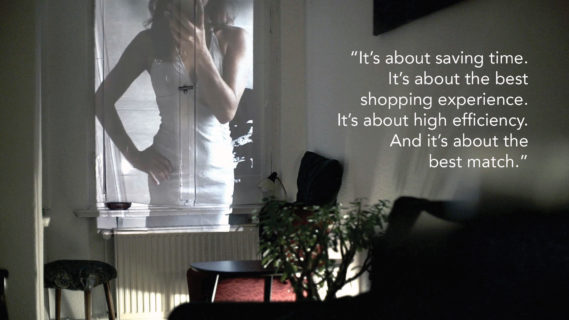

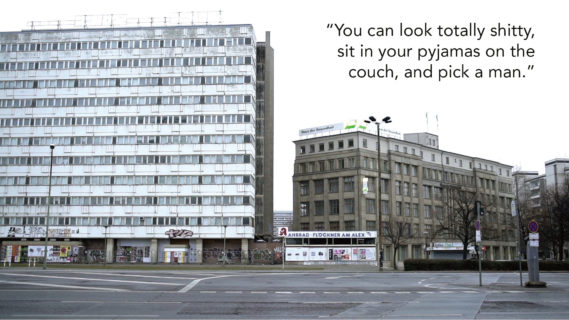

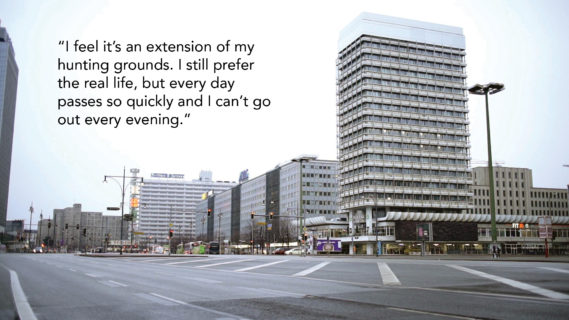

Reasons for using the app varied. For some, it presented opportunity to meet potential partners without the need to go out every night. Others praised the app’s efficiency and compared its consumer-like functionality to “choosing a man from a catalogue.” Tinder may be synonymous with “hookup culture,” but interviewees also talked about looking for less overtly physical or casual forms of social engagement and described it as a space to communicate with others.

Anne Chahine

The idea of finding “the one” and that searching for a romantic partner in the digital realm can increase one’s chances of meeting someone in “real life” wove through all these stories. And this experience is not confined to these Berliners: Helen Fisher (2016) argues that while dating technology may be changing courtship, the human brain has evolved to always seek romantic love and long-term partnership. The transition from online to offline was often a positive one for people, a defining moment of endless love-related possibilities: “At some point you have to step out of the platform. And once you make that step, anything can happen.”

Anne Chahine

The visual concept of the short documentary is inspired by the most prominent bodily experience that my interviewees described while using the app: that of connecting to thousands of people while physically being alone. I found the visual translation of this sensation during the early morning hours in the wide urban landscapes of Berlin. Streets and places that usually bustle with thousands of people were almost deserted at this time of day. The persistent emptiness of these spaces provides the viewer with an almost meditative visual background that leaves enough room to engage and reflect on the variety of the stories being told.

Anne Chahine

Anne Chahine is a PhD candidate in the Department of Anthropology at Aarhus University and co-editor of NAFA-Network, the newsletter of the Nordic Anthropological Film Association. Looking for Mr. Right Now has been screened at film festivals around the world including the Society for Visual Anthropology Film and Media Festival (2016) and the Tripoli International Film Festival (2016).

Cite as: Chahine, Anne. 2019. “Looking for Mr. Right Now.” Anthropology News website, January 25, 2019. DOI: 10.1111/AN.1071