Article begins

In Brazil and Kentucky, rural populations are producing media content to take on marginalization and discrimination in their communities.

After Donald Trump’s election in 2016, I started noticing a troubling discourse circulating among graduate students and professors on campus and at conferences. Trying to make sense of what happened, people began blaming the ignorant rural poor, collapsing complexities of rural life into narratives about “Trump’s America” or the elusive “white working class.” As a rural Kentuckian and first generation college student, I was discouraged by these discourses. How could the same people who are experts in Marxist political economy or intersectional feminism suddenly make such blanket assertions about rural people?

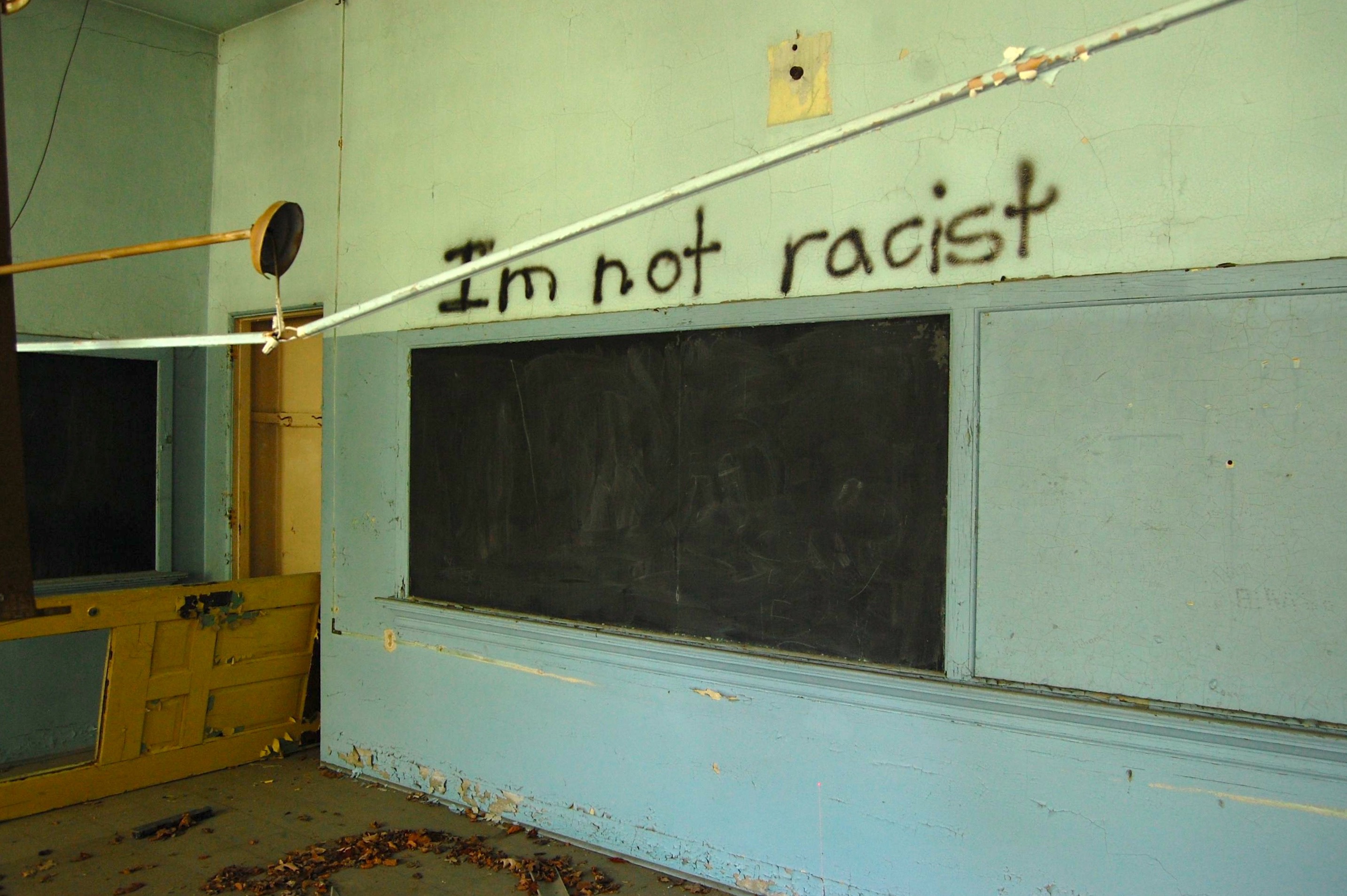

“I’m not racist” graffito in an abandoned rural school in Harlan County, Kentucky. Shelly Biesel

In the United States and other places around the world, rural people are battling intersectional identity-based oppression and stereotypes that conflate rurality with ignorance or extreme conservativism or both. My research in rural communities in Northeast Brazil and Central Appalachia has illuminated how internal and external discrimination can profoundly shape rural identities and struggles. Both Northeast Brazil and Central Appalachia have endured persistent poverty, poor access to education, extreme ecological degradation associated with extractive economies, and absentee land ownership. Both are commonly deemed backward or othered within broader national discourses. Both regions receive a near constant stream of people arriving from elsewhere and making assertions about who they are, and what is best for their communities.

Remarkably, despite these challenges, local people in both regions are mobilizing creative media and digital platforms to fight intersectional oppression within their communities as well as these external stereotypes and discrimination. One inspiring example is the Women’s Center of Cabo do Santo Agostinho (CMC) in Pernambuco, Brazil, which uses radio programming to contest pervasive race, class, sexuality, and gender-based oppression historically entangled with the region’s sugarcane plantation economy. After a Brazilian census identified the region as having one of the highest illiteracy rates among women, the CMC organized a radio program (Rádio Mulher) that would reach illiterate women working in the cane fields or otherwise remote areas. Rádio Mulher programming addresses violence against women; confronts racism; and discusses cordel poetry (folk-popular poetry), cooking and medicinal knowledge, and women’s health. On Fridays the thematic focus shifts to local environmental justice issues, most recently the oil spill that inundated 2,100 kilometers of Northeast Brazil’s coastline. The program also employs a group of women as radio technicians, announcers, and producers. Through Rádio Mulher and other initiatives, the CMC offers women lasting skills to think about and represent their own interests on the airwaves. CMC’s initiatives also facilitate participation with broader networks of activists working to end identity-based discrimination and rural marginalization in Brazil.

Much like sugarcane plantation agriculture in Pernambuco, the coal industry has profoundly shaped socio-ecological and economic dynamics in rural Appalachian Kentucky. And yet, for the past 50 years a community organization called Appalshop has refused to let coal industry narratives or Appalachian stereotypes define the region. Originally a War on Poverty initiative, Appalshop has evolved into a multifocal media institute dedicated to using film production, community radio, and other creative platforms to represent a diverse array of Appalachian perspectives and experiences. Appalshop has artfully crafted films about everything from folk medicine, to mining-related environmental disasters, to women who work in fast food restaurants. Their annual summer workshop (Appalshop Media Institute) teaches regional youth digital media skills to help them communicate their own stories about Appalachian identities and struggles. While Appalshop does not identify as a strictly feminist organization, their programming often embodies a politics of care, collaboration, and recognition of how an individual’s challenges are indelibly linked to broader liberatory struggles—in other words, a radical feminist praxis.

Woman entering Appalshop building. All Access EKY

Notably, the radio program Calls from Home broadcasts voicemail messages from family members to incarcerated individuals in one of seven regional prisons and correctional units. In many cases, messages broadcast over the airwaves are the only form of communication for people who cannot afford the long journeys to visit prisoners or expensive collect calls. Feminist Fridays radio programming airs positive, intersectional feminist messaging and empowering women-focused music. Beyond radio, Appalshop has led a program called All Access EKY, a multimedia initiative that uses storytelling, video, and web platforms to promote discussion and education about sexual and reproductive health. Working in 10 counties in rural Appalachian Kentucky, All Access EKY collaborates with healthcare professionals and employs regional youth to produce media content promoting “awareness, acceptance and access to reproductive healthcare in their home communities.” Media content is distributed to broader audiences to build regional knowledge about local reproductive health challenges. The initiative’s website houses relatable and often humorous video testimonies of local people’s struggles to get accurate information about birth control or abortion, among other stories

Within contemporary ”rural emancipatory struggles” (Scoones et al. 2018), women, LGBTQ+, and racialized groups are mobilizing diverse media platforms to fight for education, antidiscrimination, environmental justice, and general recognition (see also Ryan 2019). This points to the need for intersectional understandings of rural people as much as any other population. Through attending to how compounding facets of identity shape differential life experiences, intersectionality has complicated single-axis understandings of marginalization and resistance (Cho et al. 2013). An intersectional lens can help us to move past traditional understandings of rural places as “hopeless, helpless… and White” (Brown et al. 2016, 327).

To be clear, rural places are by no means diverse, egalitarian utopias. Certainly, rural communities struggle with as much identity-based discrimination as any other place. Yet, the above stories complicate monolithic narratives of rurality and challenge us to appreciate the nuance that exists within rural contexts. One way we can do this is through engaging with the diverse media platforms that rural communities are already creating to share their own stories about the places where they live. By refusing to listen to stories that challenge our own stereotypes about rural people, we deny their validity as an important or even central aspect of rural identity. Or worse, we miss the chance to be allies in rural struggles for better lives.

Shelly Biesel is a PhD candidate in ecological anthropology at the University of Georgia, where she studies gender, race and rural energy development.

Emily de Wet and Megan Steffen are co-editors for the Association for Feminist Anthropology. For more information or with interest in publishing through AFA on AN, please contact us at [email protected] or [email protected].

Cite as: Biesel, Shelly Annette. 2020. “Radical Media Challenges Rural Stereotypes.” Anthropology News website, February 24, 2020. DOI: 10.1111/AN.1357