Article begins

Lessons on Race, the Supreme Court, and the Legacy of Franz Boas

One hundred years ago, in fall 1924, a Chinese immigrant in the Mississippi Delta launched the first of two court cases that sought admission for Chinese children into public schools reserved for white children. Lum v. Rice (1927) was the first challenge to school segregation to reach the U.S. Supreme Court. Lun v. Bond (1929) followed. In both cases, the U.S. Supreme Court supported the Mississippi Supreme Court’s denial of equal opportunities to the children, and the contorted arguments about racial classifications that justified the decision, thus fixing in national law a more exclusive and rigid definition of “white” than had actually existed in everyday practice in the Delta. One hundred years later, history is echoing itself as immigration and racial categorization—and the Supreme Court’s role in adjudicating them—have again become critical issues. In both eras, a populist politician helped to inflame public sentiments—a Mississippi governor and senator in the 1920s, and a U.S. president in the 2020s.

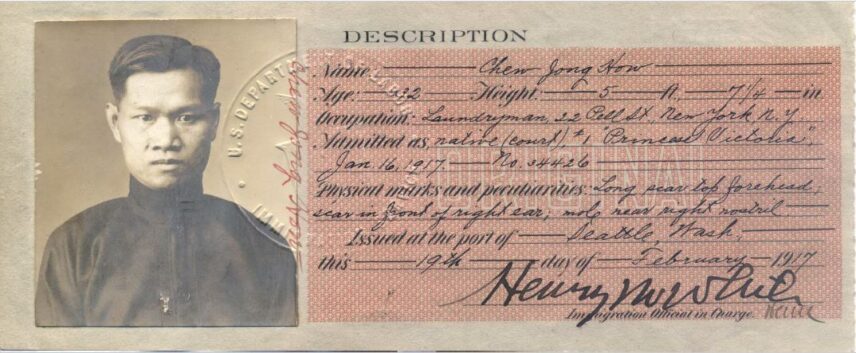

Nine-year-old Martha Lum, a Mississippi-born child of Chinese immigrants, was denied admission to the new Rosedale Consolidated High School despite having attended the white public school the previous year. San Francisco-born Chew Howe, who owned a grocery store in a small town eight miles away, sued the school’s trustees and the state superintendent of schools on Martha’s behalf. Howe and Martha had standing to sue because both were American citizens according to the birthright clause in the Fourteenth Amendment—which no one challenged at the time.

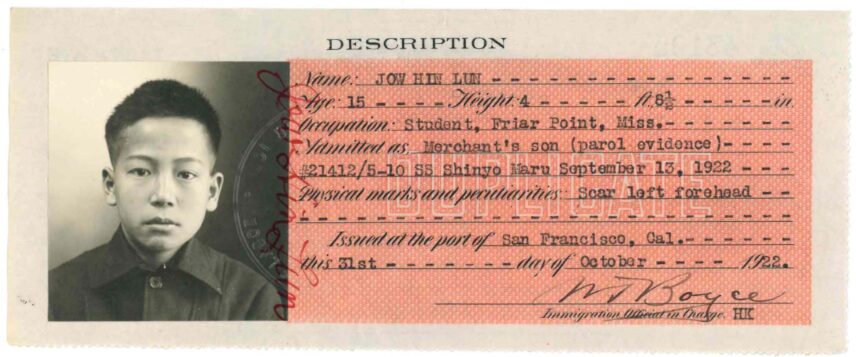

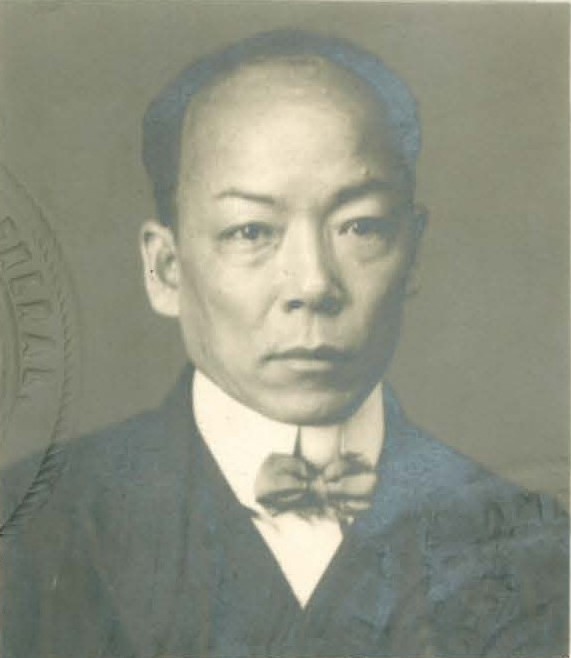

In a nearby county, the same thing happened to seventeen-year-old Hin Lun Jow when the new Dublin Consolidated High School opened. A year later, his father, Tsee Fung Jow, sued on his son’s behalf. He had immigrated in 1916 and brought over his son in 1922, and both were still non-citizens; they cited the 1868 U.S.-China Burlingame Treaty, which stipulated that Chinese citizens in America had the same rights as American citizens. No one challenged that claim, either, although Congress had already violated the treaty by passing the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act banning the immigration of Chinese laborers. Months before Martha’s suit, the U.S. Congress had responded to a growing public panic by passing the Johnson-Reed Immigration Act in an attempt to protect the dominance of the white race by setting nationality-based immigrant quotas and banning Asian immigrants altogether.

The two lawsuits were supported by the United Chinese Merchants Association – Tennessee, Arkansas, Mississippi, which had been established a few years prior by business leaders of the Delta Chinese community, an enclave that dated back to the 1870s and numbered over 300 by the time of the lawsuits. These men were able to legally enter the country and remain because they owned small grocery stores, which qualified them as “merchants”—a category exempted from the Exclusion Act. They exploited a unique economic niche created by the Jim Crow segregation laws that prevented grocers from serving both white and black customers. They sold basic necessities—such as flour, cornmeal, sugar, molasses, and meat—to the black tenant farmers who constituted nearly eighty percent of the Delta’s population. As one octogenarian grocer said of the elite white owners of the cotton plantations, “They needed workers, and the workers needed us, so they needed us.”

Earl Brewer vs. Theodore Bilbo

The merchants hired Earl LeRoy Brewer (1869-1942), a self-made man, lawyer, and cotton planter who had been governor of Mississippi from 1912 to 1916. The court fees for both cases ultimately amounted to the equivalent of $24,520 in today’s dollars, no small sum in a time when the Delta was in deep recession due to a crash in cotton prices. As governor, Brewer had been known for his attempts to reign in government corruption and lynching, and to attract immigrants to his labor-starved state—positions that made him many political enemies, foremost among them Theodore Bilbo, his (separately-elected) lieutenant governor. Bilbo’s political ascent was propelled by his base of lower-class white farmers and workers who, like him, proudly claimed the identity of “redneck.” Despised by the elites for his inflammatory rhetoric, sexual immorality, and corruption, he was investigated or prosecuted multiple times but escaped consequences. With consecutive terms prohibited, Bilbo succeeded Brewer as governor from 1916 to 1920, then a second term from 1928 to 1932, and then three terms as a U.S. senator from 1935 until his death in 1947. White supremacism was on the rise, with Bilbo as the epitome of its worst excesses. Brewer left politics in frustration at his inability to stop Bilbo and “Bilboites.”

Anthropology and Race

The State Constitution of Mississippi stipulated that “separate schools shall be maintained for children of the white and colored races.” But it did not define “colored.” In many towns, whites often tolerated a few Chinese children in the white schools, but even a slight increase in numbers could spark opposition. So-called “negro schools” were few and far between, and inferior. Chinese parents, who held the Confucian belief in the utmost importance of education, always improvised better options.

Racial segregation and immigration were intertwined political issues, and the discipline of anthropology was thick in the middle. In 1908, the Dillingham Commission, a congressional joint committee, was formed to make recommendations on immigration policy. It hired Franz Boas, a professor of Anthropology at Columbia University, and his students to conduct research on immigrant populations. Applying the methods of both physical and cultural anthropology, they demonstrated that races did not exist as physical realities, clear dividing lines between races did not exist, and ideas about race were nothing but rationalizations for the belief that white races were superior. The Commission largely ignored their scientific findings, and its own conclusions later justified the Johnson-Reed Act. However, Boas and his students, including Ruth Benedict and Margaret Mead, reached an ever-larger audience through their teaching and publishing. During World War II, Benedict co-authored a public service pamphlet, The Races of Mankind (1943), which argued, more strongly than Boas had, that there is only one “universal Human Race.” It became one of the most widely distributed pamphlets of its time.

Inequality and Race in the Court Cases

In 1924, Brewer submitted a succinct brief to his friend, Eleventh District Circuit Court Judge William A. Alcorn, centered on two arguments. First, the right to attend a public school is a valuable right, and “on account of her race or descent [Martha Lum] is being denied the equal protection of the law” guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution. Second, the school board had made “an unreasonable and arbitrary classification of the residents based solely upon color,” and, “The Chinaman is not a ‘colored person’ within the meaning of our laws.” He did not cite Boas, but he sounded like a Boasian when he pointed out that “this classification made by the school authorities exclusively for the benefit of the white race is a discrimination against the other race.” Judge Alcorn agreed, citing legal precedents and stating that he had never heard the term “colored” applied to “the Indian, who is red, the Mongolian, who is yellow, or Malay, who is brown.” He used the five-color racial categories (white, black, red, yellow, brown) first put forward by Johann Friedrich Blumenbach in 1776.

Alcorn ordered the school board to admit Martha. A year later, he did the same for Hin Lun. Both school boards appealed the decisions to the Mississippi Supreme Court, which overturned Alcorn’s decision, ruling that all people who are not white or “Caucasian” are “colored,” based on the reasoning that “the dominant purpose of the Constitution in providing for the separation of the races was to preserve the purity and integrity of the white race.” The court opinion started by acknowledging that there is no clear way to divide humans into races, because “the color test alone” (i.e., classification based on skin color) would eventually result in a gradual merging of the races. This was evidently unthinkable to the court because, “Race amalgamation has been frowned on by Southern civilization always.” After this disclaimer, the court launched into a meandering, fourteen-page discussion, explicitly citing Blumenbach, about how “judicial decision and the science of ethnology” classify humans into races.

But the important issue was that Martha had been deprived of equal opportunities under the law. When neither the state nor federal supreme court seriously engaged with this fact in her case, Brewer doubled down on demonstrating the inequality between white and “negro” schools in the circuit court hearing for Lun v. Bond, examining white witnesses in excruciating detail about the inferior quality of “negro schools.” He asked the County Superintendent of Education whether Hin Lun could obtain an education at a “negro school” equivalent to that in the white public schools of the county. The Superintendent replied, “Unquestionably he could not.” Judge Alcorn used this as a major reason for his decision, stating, “To hold that this was a school in the meaning of section 201 of the [Mississippi] Constitution would be a farce.”

Everyday Racial Prejudice

The testimony of the authorities who excluded the Chinese children revealed that they felt threatened by people whom they regarded as outsiders, and had given little thought to convoluted legal or academic arguments about what the state constitution meant by “colored.” Six years later, the state attorney general, Rush H. Knox, described his attitude under oath when Brewer dragged him into court with accusations of illegal meddling and financial corruption in the two cases. He explained that he had intervened because, if the U.S. Supreme Court were to allow “colored” children into white schools, “They would soon have some yellow kinks there and I could not see that.” He was exonerated by the Mississippi Supreme Court.

In the circuit court hearing, Brewer asked a trustee of the Dublin school why he excluded Hin Lun. His first answer was that it was because he was Chinese. In addition, “Filth. He was filthy, and I didn’t feel like our children were there for that.” When Brewer probed further, he explained, referencing the remittances that the Chinese sent to their home villages in Guangdong province,

“They don’t have anything to do with us, they don’t associate with us, they get all the money they can and send it to China, or somewhere.”

Brewer asked, “In other words, competition in business?”

“Absolutely.”

“And this is the reason he was excluded from the school?”

“Yes, sir.”

The U.S. Supreme Court issued unanimous decisions in both cases affirming that school segregation was within the constitutional power of the state, a position that was not reversed until Brown v. Board of Education in 1954. The opinion in Lum v. Rice was written by former U.S. president William Taft, Chief Justice at the time. In Lun v. Bond, the court reaffirmed its decision in Lum v. Rice and added that, since “negroes” were citizens, there was no violation of the Burlingame Treaty in giving Chinese citizens the same rights as American “negroes.”

Theodore Bilbo died in 1947, while the U.S. Senate was blocking him from taking his seat during an investigation of his suppression of black votes. He left behind Take Your Choice: Separation Or Mongrelization, a self-published manifesto that contained a rant against Franz Boas, “this immigrant from Germany” and Jew. Boas’s “disciples,” he maintained, had been “vaccinated with the virus of poison of Boas’s teachings,” namely, his “evil, disastrous, and racial suicidal preachments and his insane and corrupt doctrines of miscegenation, amalgamation, intermarriage, and mongrelization.”

Lessons

What lessons can we take away from this history? Yes, the Boasians lost the battle of the moment, and Blumenbach’s hoary racial categories were applied in state and federal cases from 1870 to the 1950s. But Boas’s ideas eventually took root in a different era, and today he is recognized as the founder of American anthropology. Scientific ideas about race still compete with the centuries-old articles of faith that justified colonialism and slavery. Nevertheless, we should never underestimate the power of anthropology’s ideas: anthropology has changed the world, and still has the potential to do so.

Postscript

In 2022, Bilbo’s statue was removed from the capitol building in Jackson, Mississippi.

Thirty-seven years after Earl Brewer died at the age of 72, his great-granddaughter took an anthropology class and became “vaccinated with the virus of poison of Boas’s teachings.” I am that great-granddaughter.